Big Jay McNeely Interview: 13th July 1991

On the 16th September 2018, saxophonist Big Jay McNeely died peacefully in Moreno Valley, California. There were few obituaries to note his passing; in death, as in life, true recognition of his very real contribution to the birth of rock n’roll had again eluded him. Most rock history books credit the first rock n’roll record as being ‘Rocket 88’ by Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats from March 1951, while others claim it was ‘The Fat Man’ by Fats Domino from December 1949. But Big Jay McNeely’s ‘Deacon’s Hop’ was recorded in January 1949 for the Savoy label, hitting the number one spot on the Race Chart (later renamed the R&B Chart) in February 1949, and is surely a stronger contender or the honour. It was followed by ‘Wild Wig’, which featured briefly on the chart, with Big Jay backing up his newly found chart celebrity with one of the most spectacular acts in popular music. His powerful stage presence and high energy show created hysteria among his teenage audiences and he was soon making the news as nightclub owners, fearing pubic disorder, were forced to summon the police to try and prevent things getting out of control. This was surely was the real beginnings of rock n’roll. He may have been the original ‘honker and screamer’, but he was also something more, a naturally gifted showman who was not content until he had the crowds crawling up the walls with excitement, whether it was a small club of fifty people or an audience of five thousand at Los Angeles’ Olympic Auditorium.

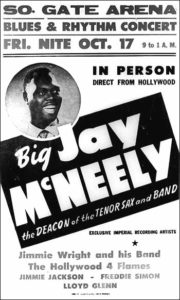

Photo Kind Permission of The Bob Willoughy Collection

As The New York Times has noted, “At times his theatrics prompted white nightclub owners to summon the police to avert what they feared would be rioting by hysterical teenagers.” Rock music has always been something more than music, it’s oppositional (to the dominant musical culture), it’s sexual, it’s emotional, it’s rebellious and and Big Jay provided all this to American teenagers seeking escape and release from wartime austerity; donned in a yellow or purple suit, his stage act grew in stature, “[his] shows were increasingly covered by the press, in part because of the name recognition his hit guaranteed, and they in turn reported in sensationalistic headlines the pandemonium McNeely was creating in audiences,” said the Spontaneous Lunacy website, in their well observed History of Rock n’Roll Song by Song. “The music, the wild performances, the fans crazed reactions and the stunned reaction to it all by the media fed off one another and firmly established rock’s notoriety in the process.”

Although he had formally studied the saxophone as a teenager and started off hoping to make it in jazz — he was encouraged in this by Charlie Parker who befriended him in 1946 (Big Jay’s mother even did Parker’s laundry for him), and having played in a band with Sonny Criss and Hampton Hawes, both of whom would enjoy distinguished jazz careers — his first professional break came with the Johnny Otis band at the Barrelhouse Club in Watts, Los Angeles playing an early version of rhythm and blues. Big Jay had made something of a local reputation for himself by wiping the floor with the competition on amateur nights at the Barrelhouse, prompting Otis to add him in his own band. At 21, Big Jay had no inhibitions about choosing the hedonistic pleasures of rhythm and blues rather than the aesthetic joys of jazz because R&B suited his natural exuberance — if the crowds responded to honking and squealing then that’s what he gave them. It wasn’t a step down to vulgarity as it was to the previous generation of sax players, for Big Jay it was a step up to recognition. He was soon the star of Johnny Otis’ band, featuring on Otis’ recording of ‘Barrelhouse Stomp’ for the Excelsior label in December 1948.

His fast developing penchant for showmanship and an easy command of his tenor saxophone brought him to the attention of the Savoy label, with whom he signed in late 1949, as Big Jay describes in this interview. When ‘Deacon’s Hop’ hit it big he thought he was ready for the big time. But when he played Clarksville in Tennessee, he failed to go over with the crowd, despite his best efforts, During his second set he started playing on his knees — nothing. Then he tried laying on his back and that was it, ‘That broke the spell,’ he said in a 1980s interview, ‘people began screamin’ and hollerin’. After that I thought, “I’m gonna try that again” and it worked everywhere through Tennessee and Texas — this was for blacks first, of course — but when I got back to the West Coast and began doing with the [white] kids…Wow!’

By the early 1950s, Big Jay had become a huge draw, on one occasion upstaging the whole Lionel Hampton Orchestra with Ebony magazine even carrying a spread of him blowing in the street during a performance at the Oasis Club in Los Angeles. On one occasion when playing the Eagle Ballroom he marched out of the club playing his honking, driving riffs, his ecstatic audience following him, and was arrested for disturbing the peace. On a tour with the Top Ten Revue he opened for Little Richard, who told him, ‘You’re the only cat who can warm them up for somebody like me!’ A Downbeat feature headlined, ‘Big Noise in R&B: McNeely, McSqueally — Either Way You Pronounce It, It Means Box Office’.

In my interview with Big Jay, I began by asking him what he considered the highlights of his early years and he immediately responded: ‘Well, I broke up the Johnny Rae sessions in California!’ He didn’t elaborate. At the time, Johnny Rae was one of the biggest pop stars in the U.S., a Columbia recording artist who sold records in their millions. Later, on researching the significance of Big Jay’s remark in the pages of Downbeat magazine, I found the answer: ‘[Big Jay] was engaged as one of the subsidiary acts to appear on the Johnny Rae show here at the Shrine Auditorium last month. Not only did he steal the show, but it was obvious that of the crowd that turned out, a larger number had paid to hear Big Jay rather than Johnny Rae or the other supporting attraction, Harry James.’

But Johnny Rae wasn’t the only big star to be upstaged by Big Jay. As he related it in a 1980s interview: ‘My drummer’s wife knew Nat’s [‘King’ Cole] first wife Nadine, and he came by the little garage where we used to rehearse. “Keep up the good work,” he told us, “You’re going to make it!” I really always respected him for that, but later we played a gig together in Oakland. I really got the people built up, I’m really walkin’. I got the crowd in such a frenzy they didn’t want to hear no singing. Nat came over to me and said “You’ll never work with me again.” I thought he was kidding but I was all set up for a big GAC tour with Nat Cole and Sarah Vaughan and they ended putting Louis Jordan in there. That hurt me, but I’ve always had the highest respect for the guy.’

Somehow, Big Jay never really made the big time, as he ruefully reflects in the interview. But he was not bitter; despite his wild, slightly unhinged image, he remained a deeply religious man who remained a devoted Jehovah’s Witness to the end of his life, something he recounts in this interview. A true professional, he gave of his best every time he played. His stage act was an acknowledged influence on Clarence Clemons of Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, and a young Jimi Hendrix, who adopted some of his moves into his own act. His control and use of otherworldly shrieks from the saxophone was adopted and distorted in the name of art by free jazz exponents such as Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, but as The New York Times observed, “The poet Amiri Baraka detected something more disruptive — and culturally more pressing — than mere unruliness in Mr. McNeely’s performances. In his book Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963), he wrote that he heard Mr. McNeely’s blaring riffs as a “black scream,” an expression of individuality and protest in the face of racial oppression.”

In the early 1950s, Big Jay McNeely was, as The Spontaneous Lunacy website points out, “nothing like you found anywhere else in popular music at the time. [He] pranced through the aisles amongst the throngs of screaming fans and laid on his back on stage with his feet in the air blowing to the heavens. When he dropped to his knees as if worshiping a righteously down and dirty rhythmic god it caused a generation of followers to find something akin to religious ecstasy in these unholy displays, fellow congregants at the altar of rock ‘n’ roll.” In 1950 and 1951, nobody embodied the potential to change the popular musical landscape more than Big Jay McNeely, and ‘Deacon’s Hop’ was the song that started it all, yet to this day he is still has not been acknowledged in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.