Charlie Haden “The Ballad of the Fallen” — Forgotten Jazz Classics

Charlie Haden’s 1983 album The Ballad of the Fallen was described by The Independent newspaper as “One of the greatest jazz albums ever.” Arranged by Carla Bley, who performed the same task for the album’s predecessor, Liberation Music Orchestra, from 1970, both were blatant protest albums, the former against America’s meddling in the affairs of South America, the latter against the Vietnamese War. Interestingly, both were released at a time when the Republican party held office.

Charle Haden and the Liberation Music Orchestra in the 1980s: (l-r) Bob Stewart (tuba); Haden (b); Sharon Freeman (fr h); Mick Goodrick (g); Herb Robertson (t); Paul Motian (d); Stanton Davis (t); Ken McIntyre (saxes); Joe Lovano (tenor sax); Dewey Redman (tenor sax).

Charlie Haden Liberation Music Orchestra was recorded when America was in political and social turmoil. The Civil Rights and anti-Vietnam war protests were at their height, the President of the United States, his Attorney General and the charismatic leader of the Civil Rights movement, Dr. Martin Luther King, had all been assassinated and the incoming President, Lyndon Johnson, faced the prospect of defeat in Vietnam. It was almost as if America had turned in on itself and no-one was sure where it would all end.

“The thing that concerned me in 1968, when I sitting in a car outside the club I was playing and listening to the news,” reflected Haden when I interviewed him in August 2005, “Was that Nixon had just bombed Cambodia, and all these people were killed. The Democratic convention was going on in Chicago and all these people had been arrested, and so that’s when I started thinking about protest.” He contacted Carla Bley, and together they came up with Liberation Music Orchestra, inspired by folk songs from the Spanish Civil War that produced the trilogy “El Quinto Regimento,” “Los Cuatro Generales” and “Viva La Quince Brigade” plus three originals by Haden, three by Bley, Ornette Coleman’s “War Orphans” and Bertolt Bechet’s “Song of the United Front.”

Today, protest albums are almost unheard of in jazz, considered a financial gamble by recording companies big and small. Even in the 1960s, a decade of protest, there was resistance to releasing Liberation Music Orchestra from Impulse! executives until producer Bob Thiele prevailed. “The protest records back then were about race, and not about the administration waging war against other countries,” explained Haden. “There’s only a few people in all the art forms, who place their concerns in what is going on — Picasso is a good example, about the Spanish Civil War — and people sometimes ask me if it made any difference to make a recording like this. What is important is that we chose to express our concerns when the circumstances warranted it out of our natural mode of expression which is music.” Today, the significance of Liberation Music Orchestra lies as much in how its political stance has long been vindicated as in the depth of its musical and social integrity.

Thomas Wolfe once cautioned that you can’t go home again. But sometimes you can. Twelve years after Liberation Music Orchestra was released, Haden did just that. His sense of justice and humanity offended by President Reagan’s policies in Latin America in general, and El Salvador in particular. Once again Haden contacted Carla Bley and the result was The Ballad of the Fallen, recorded in November 1982.

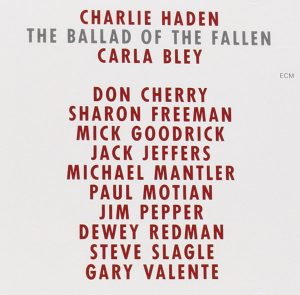

“Actually it was it was about a lot of different things, but mostly about El Salvador when Reagan was going in there,” explained Haden, who retained a core of personnel from Liberation Music Orchestra — Don Cherry (cornet), Mike Mantler (trumpet), Dewey Redman (tenor saxophone), Paul Motian (drums) and Bley on piano — to which he added Sharon Freeman (French Horn), Mick Goodrick (guitar), Jack Jeffers (tuba), Jim Pepper (tenor saxophone); Steve Slagle (alto and soprano saxes, flute, clarinet), Gary Valente (trombone) with himself, of course, on bass.

Charlie Haden

Both Liberation Music Orchestra and Ballad of the Fallen allows each track to gently elide into the next, while the overall ensemble sound on both albums evokes the Spanish village (brass) band tradition. Indeed, there are four Spanish folkloric songs from the time of the Civil War on Ballad of the Fallen — “Els Segadors,” “If You Want to Write Me,” “La Pasionaria” and “La Santa Espina.” The title track comes from El Salvador, “Grandola Vila Morena” from Portugal, “The People United Will Never Be Defeated” from Chile while “Introduction to the People” and “Too Late” are by Carla Bley and “Silence” is by Haden. The latter, with its almost ethereal unisons and Cherry’s improvisation on top is, in its simplicity, humble yet moving while it’s perhaps inevitable that the revolutionary fervour of “The People United” emerges as an album highlight, as moving in its way as “We Shall Overcome,” the final track on Liberation Music Orchestra. Both are models of freedom within form, with solos on most tracks using the “time, no changes” principal that seems to elicit the best from each improvisor.

Charlie Haden Liberation Music Orchestra: Haden (b); Bob Stewart (tuba); Sharon Freeman (fr h); Herb Robertson, Stanton Davis (t); Ken McIntyre (saxes); Joe Lovano (tenor sax)

In Haden’s own modest way, the aim of his Liberation Music Orchestra was to represent the unheard voice of oppressed people everywhere and to express solidarity with political movements fighting against totalitarianism. Yet even without its political subtext, the collective unity of the music of Ballad of the Fallen — and, of course Liberation Music Orchestra — remain a major achievement in jazz of their respective times. That they are still able speak to us today, in different yet equally volatile times, is a measure of their universality and their great humanity.