The 1952-3 Gerry Mulligan Quartet with Chet Baker – Forgotten Jazz Classics

In January and April 1949 and March 1950, a nonet under the leadership of Miles Davis recorded 12 sides for the Capitol label. Initially issued as 78 rpm discs, in 1955, eight sides were collected on a 10-inch LP as part of Capitol’s “Classics In Jazz” series. Three years later, with the addition of a further three tracks, all eleven of the nonet’s instrumental performances came out on a 12-inch LP under the title by which they have become known ever since — Birth of the Cool. Of the five arrangers who contributed to those sessions, Gerry Mulligan was possibly the most original and certainly the most prolific, responsible for seven arrangements, which included three of his original compositions, ‘Jeru’, ‘Venus De Milo’ and ‘Rocker’. It was an impressive vote of confidence by his peers, including Miles Davis, Gil Evans, George Russell, John Lewis and Lee Konitz; indeed Russell would later say “The most important innovator of 1950s was Gerry Mulligan”.

Mulligan had caused a stir in musician’s circles with his charts of ‘How High the Moon’ and ‘Disc Jockey Jump’ for the Gene Krupa band of 1946-7 as a 19 year-old, ‘Sometimes I’m Happy’ and ‘Godchild’ for Claude Thornhill’s Orchestra during the summer of 1948, and ‘Elevation’ for the Elliot Lawrence Orchestra of 1949. What is interesting about the Birth of the Cool sessions is how the musicians sought to evoke the tonal colours characteristic of the Thornhill orchestra with a smaller ensemble. In the event they settled on a nonet with the six horns split into three groups each an octave apart — trumpet and trombone, alto and baritone sax, French Horn and tuba — plus piano, bass and drums. Interestingly, Stravinsky had earlier used the same principal of six instruments in three groups an octave apart in L’Histoire du Soldat, although the combination he chose was cornet and trombone, clarinet and bassoon, violin and bass.

In tandem with Mulligan’s arranging skills was a fast developing facility on baritone sax after a spell playing a variety of saxophones in bands led by Tommy Tucker, Elliot Lawrence, Krupa and Thornhill, all of whom had recruited him primarily as an arranger. Having initially come under the spell of Charlie Parker, Mulligan also absorbed the lessons of Lester Young, rationalising both his playing and writing in favour of a more melodic, linear approach, even naming his music publishing company Pres Music. It remains a fascination that when Parker’s lines are slowed down to a pitch approximating that of a tenor saxophone they evoke, however distantly, Young’s lines, although hardly surprising since Young was also a formative influence on Parker. Several of Mulligan’s arrangements and originals written during this period suggest Young’s influence, such as those for Kai Winding (‘Godchild’ and ‘Sleepy Bop’ from April 1949), Brew Moore (the May 1949 Lestorian Mode session), and Mulligan’s own tentet recordings for Prestige in 1951 that reveal a departure from the angular contours of bop in favour of a smoother, less frantic form of expressionism.

In early 1952, Kerouac-like, Mulligan hitch-hiked to the West Coast where he endured a brief, if somewhat fraught, relationship with Stan Kenton. He also sat-in at the jam sessions at the Lighthouse, Hermosa Beach and the Monday night sessions at The Haig, an 85 seater club on Wilshire Boulevard at Kenmore Street. Here, in early July, Mulligan met trumpeter Chet Baker and just over a month later he approached club owner John Bennett to fill the Monday night spot with a group of his own, a quartet that did not include a piano, a proposition that was accepted and jazz history was made.

The first ‘pianoless quartet’ recording session was on August 16, 1952 for Pacific Jazz Records and came after playing five successive Monday nights at the club. ‘Bernie’s Tune’ and ‘Lullaby of the Leaves’ were released as a single in the Fall of 1952 to become a minor hit, putting both Mulligan and Pacific Jazz on the map. Mulligan often said his approach was to simplify rather than complicate and certainly his handling of ‘Bernie’s Tune’, a minor key 32 bar AABA tune then popular with musicians for jamming, could not be simpler with its unisons in the exposition of the theme, a chorus by Mulligan, a chorus by Baker, a chorus where the A sections provide the basis improvised counterpoint in a somewhat strained ‘baroque’ style, with the B section given over to a drum solo. The coda is 16 bars of AA. Equally, ‘Lullaby of the Leaves’, another 32 bar AABA song form, uses similar economy of purpose. Opening with the exposition of the theme by Mulligan (the A sections) and Baker (the B section), solos have Baker improvising over the AA sections and Mulligan the B and A sections. In the final recapitulation of the melody, the rhythm section plays double tempo against Baker’s variation of the ‘Lullaby of the Leaves’ melody over the two AA sections, prior returning a tempo for the BA sections, with Baker and Mulligan playing the B section together and Mulligan restating the A melody at the end. These fairly basic variations on theme-solos-theme suggest Mulligan was still coming to terms with the “pianoless” concept in terms of defining the roles of baritone and trumpet within the ensemble context.

The following month, on September 9, the quartet recorded for the Fantasy label, hitherto the sole province of Dave Brubeck with three 10 inch trio recordings, a 10 inch octet recording and a 10 inch quartet recording. Gerry Mulligan Quartet was similarly a 10 inch album, the original issue in red vinyl, that featured a batch of well crafted originals and it is here we hear how Mulligan was working towards an integrated “group sound”, rather than the hastily thrown together head arrangements of their first recording session, mixed with well arranged standards. Four compositions were recorded live at the Blackhawk, San Francisco and were captured using a single microphone set-up which is surprisingly effective — ‘Carioca’, ‘My Funny Valentine’, ‘Line for Lyons’ and ‘Bark for Barksdale’. The audience response to each of the four numbers was edited out. ‘Carioca’ shows off drummer Chico Hamilton to good effect, using his hands rather than sticks or brushes, while a straightforward reading of ‘My Funny Valentine’ proved to be an unexpected hit, prompting San Francisco Chronicle jazz critic Ralph J. Gleason to later credit Mulligan for “single-handedly” bringing the standard back into national popularity. In 2015 the quartet’s recording of the song was inducted into the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry for its, “Cultural, artistic and/or historical significance to American society and the nation’s audio legacy”. ‘Line for Lyons’ was a dedication to the San Francisco disc jockey Jimmy Lyons and is a 32 bar AABA song with a six bar coda. Mulligan’s descending harmony line against Baker’s lead — as Baker goes up, Mulligan goes down — immediately captures the ear. ‘Bark for Barksdale’ was written for Oakland’s Olympic basketball star and disc jockey Don Barksdale features a brisk, fragmented theme in a 32 bar AABA context and is essentially a feature for drummer Chico Hamilton. The other four numbers that comprised the album, the originals ‘Turnstile’ and ‘Limelight’ and the standards ‘Lady is a Tramp’ and Moonlight in Vermont’, were recorded at Hollywood’s Radio Recorders studios on January 9, 1953. ‘Turnstile’ is another brisk number on a 36 AABC form where C is 12 bars in length, with, unusually, a seven bar coda. Largely in unison except the middle eight and the final four bars of C, the coda is the only extended passage in harmony. ‘Limelight’ is also at a brisk tempo, and like ‘Bark for Barksdale’, features rhythmic displacement on the first four bars of a the A sections of this 32 bar AABA song.

By now, Mulligan’s little ensemble ws developing a unique and individual voice and was beginning to hit its stride through regular performance on their return to the Haig, attracting national attention and a feature in Time magazine — “The hot music topic in Los Angeles last week was the cool jazz of a gaunt, hungry young (25) fellow name Gerry Mulligan…for the past three months Mulligan has been performing in a nightclub known as the Haig…[and] drawing the biggest crowds in the club’s history”. On their next session for the Pacific Jazz label, on October 15/16, 1952, every number had something to commend it. Three are original Mulligan compositions specially tailored for the group — ‘Nights at the Turntable’, ‘Soft Shoe’ and ‘Walkin’ Shoes’ — while a fourth, ‘Freeway’, was by Baker. Mulligan and Baker had now come to terms with the way their lines stood out in sharp relief with no chordal backing and were clearly aiming for clear, uncluttered lines during the exposition of a song, whether in a leading or secondary role. ‘Nights at the Turntable’ is typical of the engaging originals Mulligan was now producing for the group. A 36 bar AAB A1 composition, the A1 section during the initial exposition of the theme lasts for 12 measures (A+4), during the solo interlude (AA Mulligan, B Baker and A1 Mulligan) A1 lasts for 10 measures (A+2) and during the final chorus and the recapitulation of the theme, A1 lasts for 14 measures (A+6).

The engaging A theme of ‘Nights at the Turntable’ opens with a motif of 4 quavers (eighth notes) played by Mulligan and Baker in unison, followed by a brief period of open and closed harmony . The middle eight and final A1 section (A+4 bars) introduces quite precise contrapuntal lines, but the return of the opening motif of A is always played in unison. Mulligan and Baker are now more confident about what they are trying to achieve, and this shows when each plays accompanying lines to the others solo — Mulligan on the A sections and Baker on the B section — these are not riffs, but engaging background figures, often improvised, of varying length and complexity that would have lost their impact competing with a piano, which would have directed them towards a more traditional ad hoc “riffing” relationship between trumpet and saxophone.

‘Soft Shoe’ and ‘Walkin’ Shoes’ (originally written for the Kenton orchestra), were both 32 bar AABA Mulligan originals that equally possess a mixture of engaging part writing and orderly, rhythmic counterpoint. ‘Soft Shoe’, a 32 bar AABA original has an interesting touch since the first four bars of A features baritone and bass in octaves, the second four bars Baker enters with a counter melody with the baritone outlining the harmonic movement in halftones (minims), a scheme that is repeated for each A section, except the final chorus, where the first two A sections Baker repeats his counter melody with Mulligan offering a variation of the theme that leads into the reprise of the B and A sections plus a three bar tag. ‘Walkin’ Shoes’ sees Mulligan again varying the ensemble textures, as he and Baker state the A sections in unison in the initial exposition of the melody, but in the final chorus, the recapitulation sees them playing an octave part. The solos are Mulligan one chorus, Baker on the AA section, then a return to exposition of the theme on B and A. In contrast Baker’s Freeway — a five bar intro leading into an ABAC form — is all hustle and bustle, sacrificing the studied interrelationship between saxophone and trumpet with a basic head-solos-head approach as each take two choruses accompanied by bass and drums leading into eight bars of bass solo on A and a recap of the theme. A point of interest here is that the C section uses material from the initial five bar introduction.

Mulligan’s next session was with a West Coast version of his tentette for the Capitol label which is included here as Mulligan’s writing for it seems to have grown organically from his work with the quartet, which actually forms the core of the ensemble. It was formed, like his 1951 East Coast unit with whom he made his debut as a leader on records for Prestige, as a rehearsal band. On ‘Westwood Walk’and ‘Walkin’ Shoes’ Mulligan succeeds in capturing the engaging characteristics intimacy of his quartet with a larger ensemble. On the former, a 32 bar AA song with A sections of 16 bars each, the emphasis is on hard swing without decibel excess, exemplified by Mulligan’s writing for the ensemble after the solo choruses that captures the poise of the smaller group.

The remaining sides appear as a logical continuum of Mulligan’s role in helping mid-wife the Birth of the Cool dates. Both his compositions and arrangements favour the kind of subdued lyricism and subtle tone colours favoured by the Davis nonet. ‘A Ballad’, with its Thornhill-like ‘clouds of sound’, is a wholly convincing — 44 bar AA1 BA song with the A sections of 12 bars and a B section of 8 bars, the whole performance comprises just one chorus of the song (plus a 4 bar tag). Mulligan would later say that much of what he wrote in the 1950s was based on what he wrote for Davis, but it was also clear he was seeking to build on his past achievements, illustrated by his deft harmonic writing on ‘Rocker’, originally from the Birth of the Cool sessions, that points the way to his Concert Jazz band formed in 1960. On ‘Simbah’ he experiments with a minimum of chord changes over an extended composition of 48 bars, in an AABAA form where the A sections are 8 bars and the B section 16 (the basic form is preceded by a 24 bar introductory passage). The A sections are confined to just one chord throughout, while the B section, except for a couple of passing chords to modulate back to the A section, is effectively based on three chords. This is was unusual in jazz at the time and a sharp contrast to bop with its rapid, complex chord changes and is a straw in the wind that points to the trend of static harmonies at the end of the 1950s. Yet Mulligan did not stop there; after the exposition of the AABAA theme he never returns to it. The rest of the composition includes transitional passages, pedal points and ostinato figures and is a miniature masterpiece of developmental writing for a small jazz ensemble; this ‘second’ section, although related to the first, is unmistakably more lyrical in content and more imaginative in conception, particularly the feeling of rhythmic suspension in the coda and again a pointer to his ingenious writing for the Concert Jazz Band. A lot happens in a short space of time, yet there is never a feeling of congestion in Mulligan’s writing, rather a logical progression of ideas, one to another.

In contrast to the static harmonies of ‘Simbah’, there are moments in ‘Flash’, a 32 bar AABA song, where new chord changes are coming at the rate of one every beat, such as the particularly affecting chromatic ascent of diminished chords at the end of each A section. Here Mulligan plays ‘arranger’s piano’, and, like ‘Ontet’ (a variation on George Wallington’s ‘Godchild’), the emphasis is on harmonic movement rather than the thematic material per se. ‘Flash’ opens like a small group performance, with piano, trumpet and alto taking successive choruses. Only at the end of the alto chorus does an ensemble emerge briefly, before a somewhat lumpy Mulligan piano solo and the introduction of the ensemble proper. It is not impossible to think Mulligan’s piano style was influenced by Thelonious Monk’s improvisations in terms of its angular contours and abrupt rhythmic displacements. ‘Ontet’, with its melody based around the ii-V-I progression, uses the group more fully, as much an exercise in tone colours as part writing. Taken together, the tentette recordings, originally issued by Capitol on one side of the Modern Sounds album shared with a Shorty Rogers’ Giants, certainly do not deserve the relative-obscurity to which they have been consigned. Not only do they among the best of what would later become known as ‘West Coast Jazz’ but they stand-up well today for the originality and modest experimentation of their conception.

With the popularity of his quartet taking off, Mulligan needed to expand the group’s repertoire quickly, so it is hardly surprising that for the final three studio sessions he turned to numbers with which he was familiar. ‘Darn That Dream’ and ‘Jeru’ had been recorded by the Birth of the Cool band, ‘Swing House’ and ‘All the Things You Are’ were derived from arrangements he had contributed to Stan Kenton’s orchestra and ‘I May Be Wrong’ was from a chart he had written for the Chubby Jackson Big Band in March 1950. Somehow, however, Mulligan’s quartet seemed at its best with medium tempo numbers in two, even succeeding in bringing a quiet integrity to the master take of ‘I’m Beginning to See the Light’, Helen Forrest’s big hit with the Harry James orchestra. With allusions to the larger ensemble with its powerful unisons, the kick they bring to the old war-horse still conveys itself to the listener decades later. ‘Tea For Two’, another piece in 2, although at a brighter tempo, provides the chords for an ingenious Mulligan variation that cleverly juxtaposes paraphrase with and witty part writing; played with zest by the quartet, the quartet had come of age in a remarkably short time.

‘Makin’ Whoopee’ is customised into the group’s carefully proscribed world of gruff melody and tactful counterpoint while ‘Cherry’ is not quite as endearing; the group’s poise and delivery at odds with the Dixieland coda. However, it’s Mulligan’s originals that that invariably enjoy a second life in the memory — ‘Motel’, for example, another 32 bar AABA composition, is built around a descending figure answered by a motif built around the interval of a 4th, an unusual interval in jazz at the time to feature in a melody line. Equally, the middle eight is based on the descending cycle of 4ths — Mulligan’s use of cycles was was surprisingly effective — in the middle eight of ‘Walkin’ Shoes’, for example, he uses descending 5ths. ‘Festive Minor’ and ‘All the Things You Are’ remained unreleased until 1983, the former, not surprisingly in F minor, would appear in versions by subsequent Mulligan ensembles on the Columbia and Mercury labels. Here, however, it does not work quite so well with just the baritone stating the theme, so reducing the group to a trio for a large portion of the performance. Equally, while both Mulligan and Baker contribute thoughtful solos to the latter, the somewhat tentative ending was probably the reason it was not selected for release at the time.

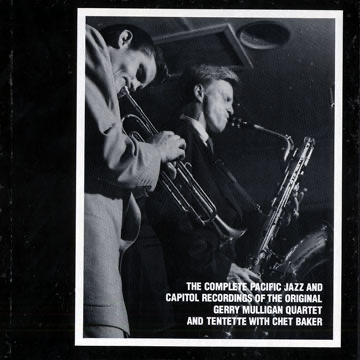

Live recordings provide have always provided jazz music’s most vital life studies, and Pacific Jazz took the opportunity of capturing the quartet live at The Haig on May 20, 1953. In all, nine tracks were recorded at the venue, although they remained unissued until Mosaic Records released The Complete Pacific Jazz and Capitol Recordings of the Original Gerry Mulligan Quartet and Tentette with Chet Baker. They provide an important documentation of this group — Mulligan has spoken of how they developed a remarkable empathy during their performances at the club, and it is interesting to hear how they interact away from the confines of a recording studio. Certainly they appear more relaxed — Baker’s solo on ‘Haig and Haig’, for example — prompted by a free and easy feeling that permeates the group as a whole. ‘My Funny Valentine’ is a reprise of their hit for the Fantasy label, played andante maestoso, while ‘Five Brothers’ is a Mulligan original dating back to a 1949 Stan Getz session. Another 32 bar AABA song which he arranged for Claude Thornhill’s orchestra a matter of weeks after it was recorded by Getz, it’s a perfect vehicle for the conversational exchanges of the trumpeter and saxophonist. By the time these live recordings , Mulligan was announcing that he had requests for numbers “From our new Pacific Jazz album”. Both ‘Aren’t You Glad You’re You’ and a rampaging ‘Get Happy’ immediately distance themselves from the sometimes introspective moods created in the studio. These are confident and sometimes exuberant (Bunker’s drums on ‘Get Happy’, for example) statements of young men at one with their art, playing for their own enjoyment as much as their audience.

The ultimate destiny of this short lived quartet became moot when Mulligan was arrested the following month for a narcotics offence and was sent to the minimum security jail at Newhall for six months. As a post-script to this remarkable little unit, Stan Getz filled-in for Mulligan at the Haig during June 1953, while he was appearing at the Tiffany Club. The 16 June recordings that exist (Fresh Sounds FSCD-1022) reveal the extent to which Mulligan had focused his ensemble with the specific end of producing a cohesive and integrated group sound. But his and Baker’s playing were shaped in service of the ensemble, most particularly in accompanying figures that spelt out the harmonic movement of chords that often presented fugue-like effects, one instrument counterpointing the other in genial interplay. In contrast, Getz’s accompanying figures are closer to background riffing than specific counterpoint per se, producing instead a rather workaday jam-session feel quite removed from the detailed ensemble characteristics that made the Mulligan’s original concept so unique.

Mulligan’s imprisonment marked the end of his association with Baker. During their year together they had developed an uncanny rapport that was frequently inspired but never again recaptured in subsequent ‘re-union’ sessions. Simply dispensing with a piano is in itself is no guarantee of success, but Mulligan’s role as conceptualist, composer and arranger in ordering the inter-relationship of the group’s instrumentation revealed the quartet’s strengths — Baker’s ingenious lyricism and Mulligan’s genial swing. Using clever part writing, judicious counterpoint and well crafted original material, Mulligan created a context where both baritone and trumpet were presented at their best within the limitations of their respective styles and the self imposed parameters of a collective group “sound”. Mulligan aimed for clarity and transparency, clear part writing and an awareness of dynamics. Avoiding the complexity of bebop, its often frantic tempos and relentless monotone somewhere between mezzo-forte and forte, Mulligan and his musicians were challenged to invest meaning in the simpler forms and devices at their disposal. This is no mean feat, as countless pianists discovered playing the simple C major triad in the opening of the second movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major, K.467. That Mulligan and Baker largely succeeded is perhaps key to the enduring appeal of this group. Yet remarkably, neither Mulligan or Baker can be said to have created a truly “memorable” solo. Instead, they constructed their improvisations within the context of each composition that resected the integrity of the compositional environment each song presented, their restraint failing to inhibit articulate construction that dew the listener in, rather like softly spoken conversation, yet on occasion appearing exciting and occasionally moving, all without recourse to artifice or grand gesture. Ultimately, however, the group lasting legacy remains in an almost perfect reduction — perhaps distillation is a better word — of Birth of the Cool, a minimalistic little brother that illustrated how less can truly be more.

Subsequently, a guiding star in Mulligan’s musical odyssey seemed to be shaped by his experiences, both as a composer and arranger, for the Birth of the Cool sessions, something he would surface throughout his career. As Mulligan once said, he was after, “[A] variety of tone colour, and the flexibility and clarity of a small band” in his writing. It somehow seemed appropriate, therefore, that he chose bookend his career by revisiting all twelve Birth of the Cool arrangements with a nonet of his own for the GRP label at the end of January 1992 (he died in 1996). He even revisited the one vocal number recorded by Davis, ‘Darn That Dream’ (that had a vocal by Kenny Hagood), with a recreation using vocalist Mel Tormé. Although Miles Davis had been enthusiastic about the project, he died in September 1991, and his role in the nonet was taken by Wallace Roney. Of the original band, only Bill Barber (tuba) and John Lewis (piano) were available, Lee Konitz, who was originally scheduled to join the group, was previously committed on the other side of the globe at the time of record date and was replaced by Phil Woods. Rounding out the group were Dave Bargeron trombone, John Clark French Horn, Dean Johnson on bass and Ron Vincent on drums. The resulting album, Re-Birth of the Cool, was a little bit like the film of a book, not quite as good as you hoped.

In June 1992, Mulligan performed in Carnegie Hall for a JVC Jazz Festival concert called “Rebirth of the Cool” with a slightly different personnel to that the recording, with Lee Konitz in on alto sax, Art Farmer responsible for the solos once taken by Miles Davis and Mike Mossman on trumpet with Rob McConnell on valve trombone, Bob Routch on French horn, Ted Rosenthal on piano, Dean Johnson on bass and Ron Vincent on drums with the addition of Ken Soderblum on saxophone and clarinet to make it a dectet (and including Mulligan, an undectet). The concert was well received, Jon Pareles in The New York Times noting, “Mr. Mulligan and Mr. Konitz were both in fine form, Mr. Mulligan gruff and swaggering on baritone saxophone, Mr. Konitz leisurely and oblique on alto. And even after 42 years, the arrangements remain enigmatic, a corrective to the brassy extroversion of the big-band era…The concert also included pieces from Mr. Mulligan’s own repertory, among them ‘Blueport’”.

The Carnegie Hall concert preceded a European tour, which included The North Sea Jazz Festival where I saw the band on July 11th, unaltered in personnel since the Carnegie Hall concert. No question about it, it was a thrill to hear the Birth of the Cool charts live, but as the recording of the original band at the Royal Roost in New York City on September 4 and 18, 1948 revealed, an average of something like an extra one minute 20 seconds on each track given over to longer solos meant the tight integration between the written and the improvised on the original 78 rpm studio recordings was sacrificed. Like Ellington’s 1940-41 sides for RCA Victor, the development of the written and improvised on the original Birth of the Cool recordings seemed in perfect balance, thanks to the three minute limitation of a 10 inch 78 rpm recording where one event led logically into the next, giving a sense of momentum as new ideas and new combinations of sounds followed closely on the heels of each another giving a sense a lot was happening in a limited time. With the Re-Birth band the solos were even longer, things in themselves rather than part of a whole, so distancing the written from improvised and the less is more ethos of the originals.

As Mulligan’s Concert Jazz Band — one of the great big bands of the 1960s — subsequently revealed, the big band ultimately proved to be the ideal context to frame Mulligan’s ability as a conceptualiser, composer, arranger and soloist. When he organised a big band in 1980, that produced the Grammy winning Walk On Water (DRG), he opened a new and unexpected chapter in his life, annually making the round of the summer jazz festivals. There was a moment on the opening track of Walk On Water, ‘For An Unfinished Woman’, where the brass, in close harmony, play a repeated two bar figure that evokes a counter line from Mulligan that fleetingly brought to mind the kind of accompaniment/obligato figures he played behind Chet Baker in the quartet all those years ago. For a moment the past became the present and the present became the past as Mulligan became his own history. It was a reminder how those 1952 recordings with Baker have stood the test of time. Ingenious, witty and well conceived, they were an early landmark in Mulligan’s career that are all too often overlooked today.