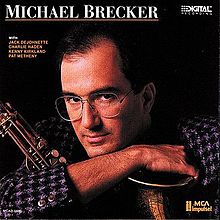

Michael Brecker “Michael Brecker” — Forgotten Jazz Classics

When he recorded Michael Brecker in 1987, it was unusual that such a major talent in jazz should have eluded making an album under his own name until he was 38 years of age, especially since he was already widely recognised as the most influential saxophonist since John Coltrane. The preeminent studio saxophonist of his generation, he had already appeared on some 700 albums by the time he came to record Mike Brecker (by the time of his death in 2007 that number had risen to over 900). His list of playing credits was as extensive as it was unique, in pop and rock music just about everyone, it seemed, from Frank Sinatra to Frank Zappa, as well as being a particular favourite of Paul Simon and Joni Mitchell with whom he also toured. In jazz, his album credits as a sideman were equally impressive, including stand-out performances on Chick Corea’s Three Quartets, Pat Metheny’s 80/81, McCoy Tyner’s Infinity and Claus Ogerman’s Cityscape.

The 1980s saw Brecker stepping out of the studio scene onto the touring circuits, both as a member of the co-operative Steps Ahead and with his own group, The Mike Brecker Band that featured Mike Stern on guitar.

The Mike Brecker Band 1987: Michael Brecker (ts); Mike Stern (g); Adam Nussbaum (d); Jeff Andrews (b).

When news that he had signed a deal with Impulse! records it was widely expected he would debut with his touring band, but in the event, he chose to re-convene what was essentially the core personnel on Pat Metheny’s 80/81 from May 1980, albeit with pianist Kenny Kirkland in saxophonist Dewey Redman’s stead. Comprising Brecker on tenor saxophone and EWI (Electric Wind Instrument, an electronic hornlike device that plays a range of sampled sounds), Kenny Kirkland piano and keyboards, Pat Metheny guitar, Charlie Haden on bass and Jack DeJohnette on drums, Mike Brecker is an impressive jazz recording by any standards, and certainly a latter day classic.

Opening with the haunting electronic tone colours of ‘Sea Glass,’ Kirkland’s piano implied a 3/4 pulse while Brecker’s exposition of the theme suggested a rubato feel (it was not) before Haden and DeJohnette move into a flowing three as Brecker opens his solo with long legato lines which give way to an increasing density of notes manipulated through a rising line to climax into the high register of the saxophone. This gradual increase in density and intensity while reaching further and further up the range of his saxophone brought a feeling of symmetry to his improvisation, despite the static harmonic movement. Something of a hallmark of his playing was his tonal manipulation through pitch bends and an alteration of the density of sustained notes by partially closing the bell-tone keys (Bb, C, C#), that gave his solos an element of vox humana.

‘Syzygy’ began as a tenor-drums duet before a statement of the theme that included both written and improvised sections. Kirkland opened his solo with right-hand figures with a minimum of (left-hand) comping but becomes more expansive as he moves to a climax, increasing the density of his line against more pronounced left-hand voicings. Brecker’s solo is on an EWI, perhaps less satisfying than a saxophone, but nevertheless he succeeds in exploiting the instrument’s potential, the performance rounded out by a thoughtful contribution from Metheny.

Michael Brecker playing the EWI

On the Mike Stern composition ‘Choices’ a polymetric effect is achieved by a slow moving melody line punctuated by a staccato motif for piano and bass. The form is AAB, with the A sections 30 bars and the B section 20 bars, but because it was in cut-time, the form feels like sections of 15 and 10 bars respectively. Throughout the bass and piano reiterate the insistent staccato motif, although in the B section, the pre-written rhythmic figures are not present in the first 12 bars, allowing for a looser rhythmic approach from Haden and DeJohnette, but the pre-written bass motif returns for the final eight bars of B, albeit embellished freely by DeJohnette. The rhythmic structure is preserved throughout excellent solos by Brecker and Kirkland in much the same way a specific rhythmic scheme is adhered to throughout Herbie Hancock’s ‘Maiden Voyage.’

Mike Brecker (ts) with Mike Stern (g), 1987.

Brecker’s close friend Don Grolnick (who co-produced Mike Brecker) was a masterful contemporary composer, and his composition ‘Nothing Personal’ provokes one of the best performances on the album. A through-composed 24 bar piece, it opens on a G minor vamp until the theme is cued. The tempo is brisk, and utilises a pre-written bass figure in cut-time that reveals the broken phrases of the theme in stark relief. Within the overall 24 bar structure, the penultimate four bars are given over to improvisation before a return to the pre-written bass line for the final four bars. The bass figure is preserved for the first chorus of every solo, but then walks for subsequent choruses. Metheny, a lucid melodicist who gloved his brilliant technique in service of the material at hand, briefly flowers before Brecker moves to centre stage with a solo of precisely articulated logic, developing motifs throughout the whole range of the saxophone before a climax using sustained tones.

‘The Cost of Living,’ another Grolnick song, and a riveting a cappella opening to ‘My One and Only Love,’ reveal Brecker’s strong, elegant ballad playing where his enormous harmonic knowledge and rhythmic mastery combine to produce two exemplary examples of contemporary saxophone playing with Metheny caught up in the drama of the latter, contributing an especially moving and graceful solo. ‘Original Rays’ (named after the famous New York pizza chain) is another feature for EWI. Brecker’s level of virtuosity on this hybrid instrument, which also permits chords, is mesmerising. He once said it made him sound like ‘a sax section from Mars’ and there is certainly something otherworldly about his a cappella introduction, something that was expanded to become a feature in live performance. An abrupt switch to tenor and the short solo that follows is dramatic as it is unexpected before giving way to a well-defined Metheny solo. The graceful execution of Brecker’s second solo sees him working towards a perfectly judged climax. It is one moment among many on Michael Brecker that reveals a player who not only was one of the most important soloists to emerge in jazz of the 1980s and 1990s, but was also a figure of such stature he numbers among the roll call of the finest saxophonists in jazz.

READ MORE CLASSIC MODERN ALBUM POSTS